Switching Loops – When Redundancy Turns Dangerous

In a switching network, redundancy is very common. We connect switches using multiple links so that if one link fails, traffic can still flow through another path. On paper, this looks like a strong and reliable design.

However, at Layer 2, redundancy comes with a serious risk known as a switching loop.

A Layer-2 switch works inside a single broadcast domain. This means whenever the switch receives:

- Broadcast frame or

- Multicast frame

it forwards that frame out all ports except the one it came from.

This behavior is completely normal and expected in Ethernet networks.

The problem starts when there is more than one path between switches.

How a Switching Loop Is Created

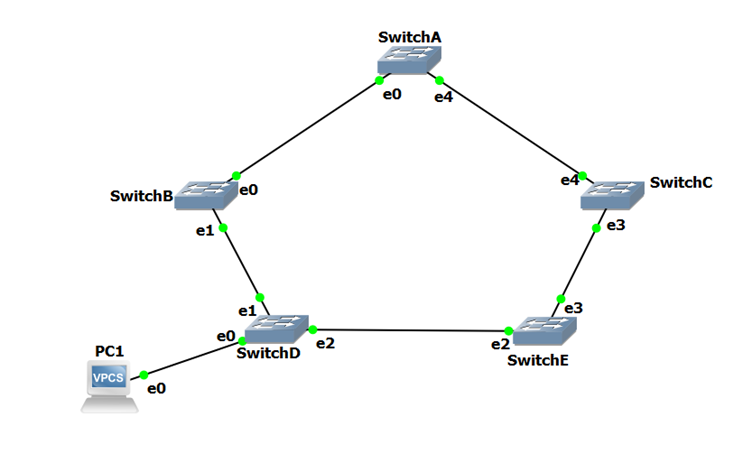

Let us understand this with a simple scenario.

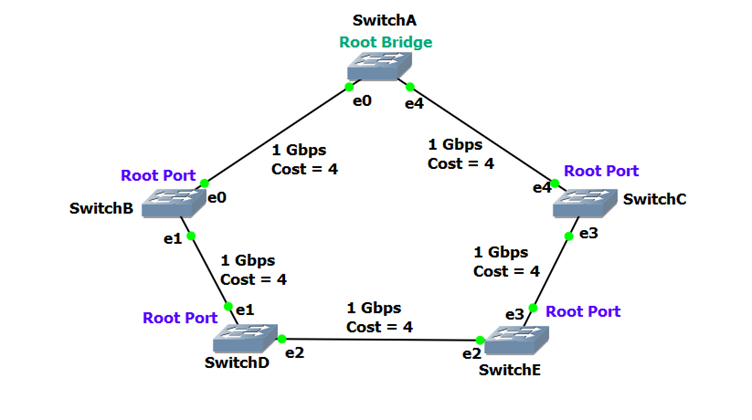

As shown in above topology the multiple switches connected together in a loop. Now assume Host (PC1) sends out a broadcast message (for example, an ARP request).

Here is what happens step by step:

- The broadcast reaches Switch D

- Switch D forwards the broadcast out all ports in the same VLAN

- This includes the trunk links connected to Switch B and Switch E

- Switch B and Switch E receive the broadcast and again forward it out all their ports

- The broadcast now reaches Switch A and Switch C

- From there, it again gets forwarded back into the network

At this point, the broadcast has no exit.

It keeps circulating through the switches again and again.

In fact, two broadcast storms are created:

- one moving in clockwise direction

- another moving in counter-clockwise direction

Since Ethernet frames do not have a time-to-live (TTL) value, these frames never expire.

They continue looping endlessly.

What Happens to the Network?

Within seconds, the network starts suffering from:

- Broadcast storms – bandwidth is fully consumed by useless traffic

- MAC address table instability – the same MAC address keeps appearing on different ports

- High CPU usage on switches – switches struggle to process frames

- Network outage – real traffic is completely blocked

The most dangerous part is that a switching loop can bring down the entire network very quickly.

In early networks, the only way to stop such a storm was:

- powering off switches, or

- physically unplugging cables

This problem made it clear that Layer-2 networks needed an intelligent loop-prevention mechanism.

Spanning Tree Protocol (STP) – The Solution to Switching Loops

To solve the problem of switching loops, Spanning Tree Protocol (STP) was introduced.

STP was originally defined under IEEE 802.1D, at a time when Layer-2 bridges were widely used. That is why many STP terms still use the word bridge, even though today we mostly use switches.

Why STP Was Needed

Network engineers faced a difficult challenge:

- Removing redundant links would make the network unstable

- Keeping redundant links would create loops

STP solved this by introducing a smart idea:

Keep all physical links, but allow only selected paths to forward traffic.

Instead of removing cables, STP logically blocks some switch ports so that loops cannot form.

How STP Works at a High Level

When STP is enabled, switches do not forward traffic blindly.

Instead, they first build an understanding of the network topology.

Each switch:

- shares information with neighboring switches

- learns about the entire switching network

- identifies all possible paths

Once this information is collected, STP:

- detects where loops exist

- blocks only the minimum number of ports required

- ensures the network becomes loop-free

A very important advantage of STP is that blocked ports are not permanently disabled.

If an active link fails, STP can unblock a previously blocked port and restore connectivity automatically.

This is how STP maintains:

- redundancy

- fault tolerance

- network stability

STP and Load Balancing (Important Note)

Because STP blocks redundant paths, traffic flows through only one active path.

This means STP does not provide load balancing by default.

If load balancing is required, technologies like EtherChannel are used, where multiple physical links are bundled into one logical link.

How Switches Communicate in STP

To build the topology, STP-enabled switches exchange special messages called Bridge Protocol Data Units (BPDUs).

Some important points about BPDUs:

- Sent out every 2 seconds

- Forwarded out all switch ports

- Sent to a special multicast MAC address

0180.c200.0000

Using these BPDUs, switches slowly agree on:

- which switch should act as the center

- which ports should forward traffic

- which ports should be blocked

STP Convergence – Reaching a Stable State

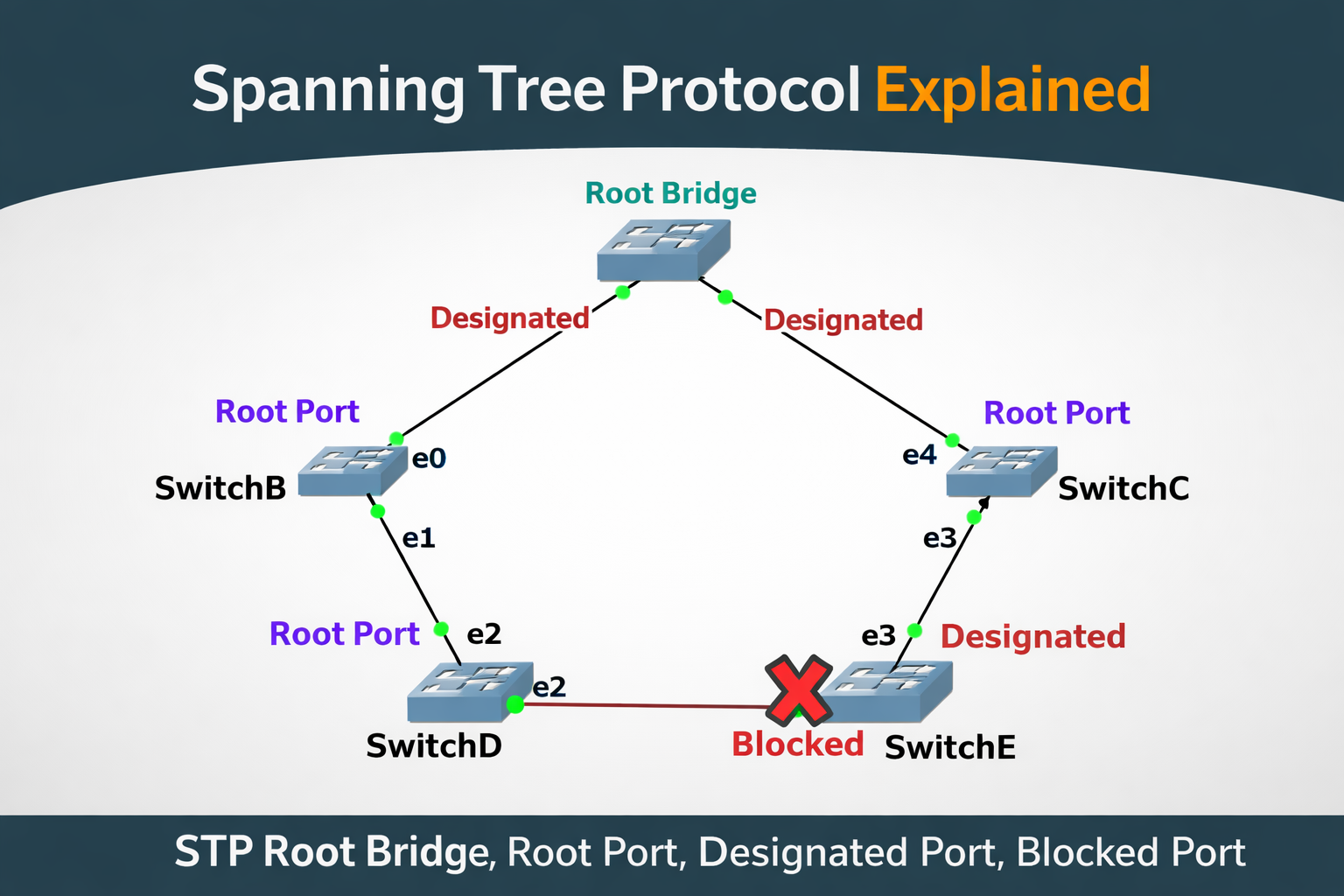

Building the STP topology is a multi-step convergence process:

- A Root Bridge is elected

- Each switch identifies its Root Port

- Designated Ports are selected on each link

- Remaining ports are placed into blocking state

Once all switches agree on these roles and no loops exist, the network is said to be converged.

From this point:

- traffic flows normally

- redundancy is preserved

- loops are eliminated

Default STP Behavior

On Cisco switches:

- STP is enabled by default

- It runs on all VLANs

- No manual configuration is required for basic protection

This default behavior has saved countless networks from accidental loops caused by mis-patching or human error.

Electing the STP Root Bridge – Choosing the Center of the Network

Once Spanning Tree Protocol is enabled, the very first thing it does is choose a Root Bridge.

This step is extremely important because all other STP decisions are based on this switch.

You can think of the Root Bridge as the reference point or the anchor of the entire Layer-2 topology. Every other switch in the network will calculate its best path towards this Root Bridge.

Why a Root Bridge Is Needed

In any group of connected switches, there must be:

- one common point of reference

- one switch that defines “the shortest path”

Without a single reference, switches would make independent decisions and loops could still form.

STP avoids this confusion by saying:

“First, everyone agrees on one switch as the Root Bridge.”

As a best practice, the Root Bridge should be the most centralized switch in the topology – usually a core or distribution switch – so traffic flows efficiently.

How STP Decides the Root Bridge

STP does not randomly choose the Root Bridge.

It uses a value called the Bridge ID, which uniquely identifies every switch.

In the original IEEE 802.1D standard, the Bridge ID consists of two parts:

- Bridge Priority (16-bit value)

- MAC Address (48-bit value)

STP always prefers the lowest Bridge ID.

Priority Comes First

By default, all switches have a priority of 32768.

Lower priority means higher chance of becoming Root Bridge.

So:

- Priority 100 is better than priority 32768

- Priority 4096 is better than 8192

If priorities are different, MAC address does not matter.

MAC Address as the Tie Breaker

If two or more switches have the same priority, STP uses the MAC address to break the tie.

- Lower MAC address → wins

- Higher MAC address → loses

This rule exists to ensure that STP always makes a decision, even when switches are configured similarly.

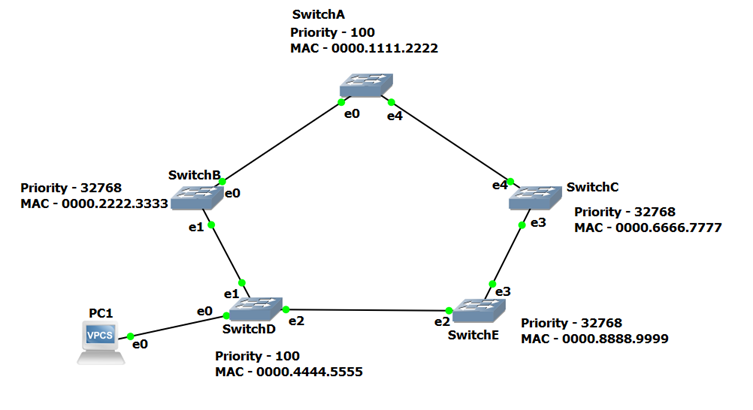

Example –

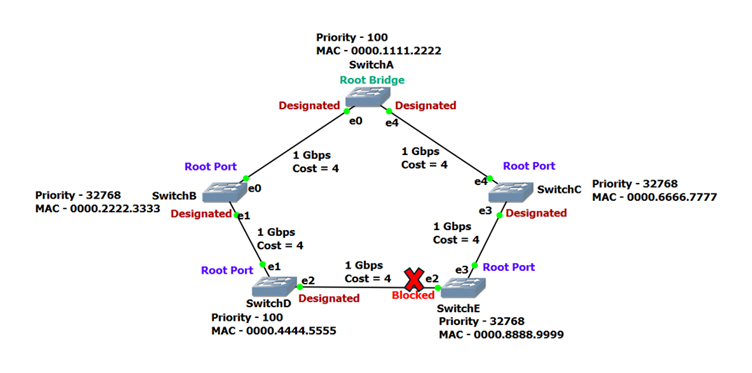

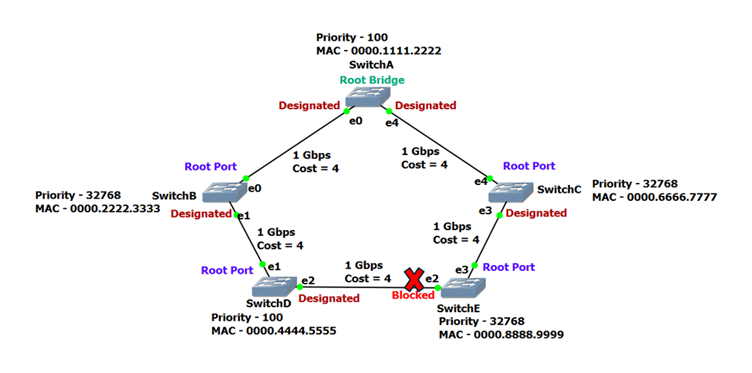

From the diagram:

- SwitchB, SwitchC, and SwitchE

- Priority: 32768 (default)

- SwitchA and SwitchD

- Priority: 100 (manually configured)

Since 100 is lower than 32768, SwitchA and SwitchD immediately become the top candidates.

Now STP compares their MAC addresses:

- SwitchA MAC: 0000.1111.2222

- SwitchD MAC: 0000.4444.5555

Because SwitchA has the lower MAC address, it wins the election and becomes the Root Bridge.

How Switches Perform the Election

Switches do not vote manually.

They exchange special messages called BPDUs (Bridge Protocol Data Units).

Each BPDU contains:

- the sender’s Bridge ID

- information about the Root Bridge

At startup:

- every switch assumes it is the Root Bridge

- it advertises itself as the root in its BPDUs

When a switch receives a BPDU from another switch:

- it compares Bridge IDs

- if the received BPDU is better, it accepts it

A BPDU that advertises a lower Bridge ID is called a superior BPDU.

Once a switch receives a superior BPDU, it stops claiming itself as root and starts forwarding the superior information.

Root Bridge Election Is Continuous

One important thing to understand is that Root Bridge election never truly stops.

STP is always listening.

If:

- a new switch is added, or

- a switch with lower Bridge ID joins the network

STP will automatically re-elect the Root Bridge.

This dynamic behavior ensures that the network always adapts to topology changes.

Identifying the Root Ports – How Switches Choose the Best Way to the Root

Once the Root Bridge has been elected, Spanning Tree Protocol moves to the second step of convergence:

identifying the Root Port on each switch.

At this point, every switch already knows which switch is the Root Bridge.

Now the question for each non-root switch becomes very simple:

“Which path should I use to reach the Root Bridge in the most efficient way?”

The port that provides this best path is called the Root Port.

What Is a Root Port?

A Root Port is the port on a switch that:

- leads toward the Root Bridge

- has the lowest total path cost

- is used as the primary forwarding path

There are a few important rules to remember:

- Each switch can have only one Root Port

- The Root Bridge does not have a Root Port

- The purpose of a Root Port is to point toward the Root Bridge

This rule helps STP maintain a clean, tree-like structure with no confusion or loops.

Understanding Path Cost in STP

STP does not choose Root Ports based on hop count or physical distance.

Instead, it uses a value called path cost, which is based on link bandwidth.

Path cost is cumulative, meaning:

- each switch adds the cost of the receiving port

- the total keeps increasing as the BPDU travels farther from the Root Bridge

The basic principle is straightforward:

Higher bandwidth = lower path cost

Lower bandwidth = higher path cost

Standard STP Path Cost Values

Below are the commonly used path cost values in classic STP:

| Bandwidth | Path Cost |

| 4 Mbps | 250 |

| 10 Mbps | 100 |

| 16 Mbps | 62 |

| 45 Mbps | 39 |

| 100 Mbps | 19 |

| 155 Mbps | 14 |

| 1 Gbps | 4 |

| 10 Gbps | 2 |

STP always prefers the lowest cumulative cost.

Bottom of Form

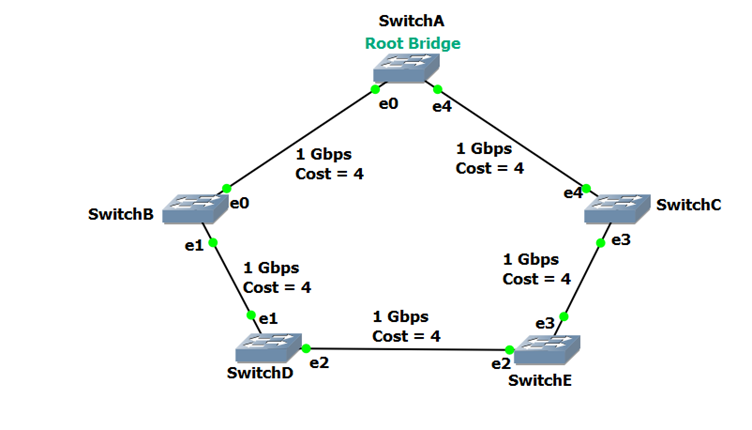

Example Topology – All Links at 1 Gbps

Consider the topology shown below.

In this network:

- Every link is 1 Gbps

- Each link therefore has a path cost of 4

Since SwitchA is the Root Bridge, its root path cost is 0.

Whenever SwitchA sends out BPDUs, it advertises a root path cost of 0.

Root Port Selection on SwitchB

SwitchB has two possible paths to reach the Root Bridge:

- Directly to SwitchA

- Path cost = 4

- Via SwitchD → SwitchE → SwitchC → SwitchA

- Total path cost = 16

STP compares the cumulative cost of both paths.

Since 4 is lower than 16, the port directly connected to SwitchA becomes the Root Port on SwitchB.

A BPDU advertising a higher path cost is considered an inferior BPDU and is not preferred.

Root Port Selection on SwitchD

SwitchD also has two possible paths to the Root Bridge:

- Through SwitchB

- SwitchD → SwitchB → SwitchA

- Total path cost = 8

- Through SwitchE

- SwitchD → SwitchE → SwitchC → SwitchA

- Total path cost = 12

Since 8 is lower than 12, the port leading to SwitchB becomes the Root Port on SwitchD.

Again, STP chooses the path with the lowest cumulative cost, not the fewest hops.

How Path Cost Is Calculated as BPDUs Travel

It is important to understand how path cost builds up as BPDUs move through the network.

- The Root Bridge advertises a BPDU with path cost 0

- When a neighboring switch receives the BPDU, it:

- adds the cost of the receiving port

- advertises the new cumulative cost to its neighbors

For example:

- SwitchC receives a BPDU with cost 0 from SwitchA

- SwitchC adds the port cost (4)

- SwitchC now advertises a path cost of 4

Next:

- SwitchE receives that BPDU

- SwitchE adds its receiving port cost (4)

- SwitchE now advertises a cumulative path cost of 8

This process continues until all switches know the best possible cost to reach the Root Bridge.

Manually Adjusting Path Cost (Advanced Control)

In some scenarios, network engineers may want to influence STP decisions without changing physical links.

STP allows path cost to be manually adjusted per port.

Example:

| SwitchD(config)# interface gi2/22 SwitchD(config-if)# spanning-tree vlan 101 cost 42 |

By changing the path cost:

- STP can be forced to prefer one path over another

- traffic flow can be controlled more precisely

This technique is commonly used in advanced designs and troubleshooting scenarios.

Why Root Port Selection Is So Important

Root Port selection determines:

- how traffic flows toward the Root Bridge

- which links stay active

- which links become backup paths

Once Root Ports are correctly identified, STP can safely move to the next step:

Designated Port selection, where forwarding responsibility is decided on each network segment.

Identifying Designated Ports – Deciding Who Forwards on Each Network Segment

After the Root Bridge is elected and Root Ports are identified, Spanning Tree Protocol moves to the third step of convergence:

identifying Designated Ports.

At this stage, STP already knows:

- which switch is the Root Bridge

- how each switch reaches the Root Bridge

Now STP must decide:

“On each network segment, which single port is allowed to forward traffic?”

That port is called the Designated Port.

What Is a Designated Port?

A Designated Port is the port on a network segment that:

- forwards BPDUs

- forwards data frames

- represents that segment’s path toward the Root Bridge

Very important rule:

- There is exactly ONE Designated Port per network segment

If two ports on the same segment were allowed to forward traffic, a loop would exist.

STP prevents this by carefully selecting only one.

Relationship Between Root Ports and Designated Ports

A port can be:

- a Root Port, or

- a Designated Port, or

- a Blocked Port

But:

A port can never be both a Root Port and a Designated Port.

Root Ports point toward the Root Bridge.

Designated Ports point away from the Root Bridge, into a segment.

Together, they form a clean, loop-free tree.

Designated Ports on the Root Bridge

Ports on the Root Bridge are special.

Since the Root Bridge already sits at the center of the topology:

- its ports have a root path cost of 0

- they are always the best path for connected segments

Because of this:

Ports on the Root Bridge are never blocked.

All ports on the Root Bridge automatically become Designated Ports.

In our topology, both ports connected to SwitchA (the Root Bridge) are designated ports by default.

Designated Ports on Other Network Segments

Now consider the network segments:

- between SwitchB and SwitchD

- between SwitchC and SwitchE

Each of these segments must have one Designated Port, even though a Root Port may already exist on that segment.

In our example:

- SwitchD and SwitchE already have their Root Ports

- Therefore, the opposite ends of those segments

(on SwitchB and SwitchC)

automatically become the Designated Ports

This satisfies the rule:

Every segment has exactly one Designated Port.

The Segment Between SwitchD and SwitchE – A Special Case

Now look at the network segment between SwitchD and SwitchE.

This segment is interesting because:

- neither port on this segment is a Root Port

- both ports are eligible to become Designated Ports

This situation tells STP something important:

A potential loop exists.

To break the loop:

- STP must select one Designated Port

- the other port must be placed into a Blocking state

How STP Chooses the Designated Port

The selection logic is very similar to Root Port selection.

STP compares, in order:

- Lowest cumulative path cost to the Root Bridge

- Lowest Bridge ID

- Lowest MAC address (if needed)

Normally:

- the switch with the lower path cost wins

- the other port gets blocked

Applying the Logic to Our Example

On the segment between SwitchD and SwitchE:

- both switches have a cumulative path cost of 12

- this creates a tie

Since path cost is equal, STP moves to the next tie-breaker:

- Bridge ID

SwitchD:

- Priority = 100

SwitchE:

- Priority = 32768 (default)

Lower priority wins, so:

- SwitchD’s port becomes the Designated Port

- SwitchE’s port is placed in a Blocking state

If the priorities were also equal, STP would then compare:

- MAC addresses

- lowest MAC address would win

What Happens to Ports That Lose?

STP follows a simple final rule:

Any port that is neither a Root Port nor a Designated Port is placed into Blocking state.

Blocked ports:

- do not forward frames

- do not forward BPDUs

- still listen for STP updates

- can become active if the topology changes

This is how STP preserves redundancy without loops.

Why Designated Port Selection Matters

Designated Ports determine:

- which direction traffic flows on each link

- where loops are intentionally broken

- how clean and predictable the topology becomes

Once Designated Ports are identified and remaining ports are blocked, the STP topology becomes stable and loop-free.

At this point, the network is very close to full convergence.

In Summary

In this blog, we walked step by step through how Spanning Tree Protocol (STP) protects a Layer-2 network from switching loops while still allowing redundancy.

We started by understanding switching loops and why they are so dangerous in Ethernet networks. Because switches forward broadcasts out all ports and Ethernet frames do not expire, a simple loop can quickly lead to broadcast storms, MAC table instability, and complete network failure.

We then introduced Spanning Tree Protocol (STP) and explained how it solves this problem by building a loop-free logical topology. Instead of removing physical links, STP intelligently blocks selected ports and keeps them as backup paths.

Next, we covered the STP convergence process in detail:

- How the Root Bridge is elected using Bridge ID (priority and MAC address)

- How each non-root switch identifies a Root Port based on the lowest cumulative path cost

- How Designated Ports are selected on each network segment to control traffic flow

- How remaining ports are placed into a blocking state to eliminate loops

By following these steps, STP ensures that only one active path exists between switches, effectively preventing switching loops while maintaining redundancy and fault tolerance.

Understanding this process makes it clear how STP keeps Ethernet networks stable, predictable, and safe even in complex topologies.