Understanding DNS: The Internet’s Phonebook

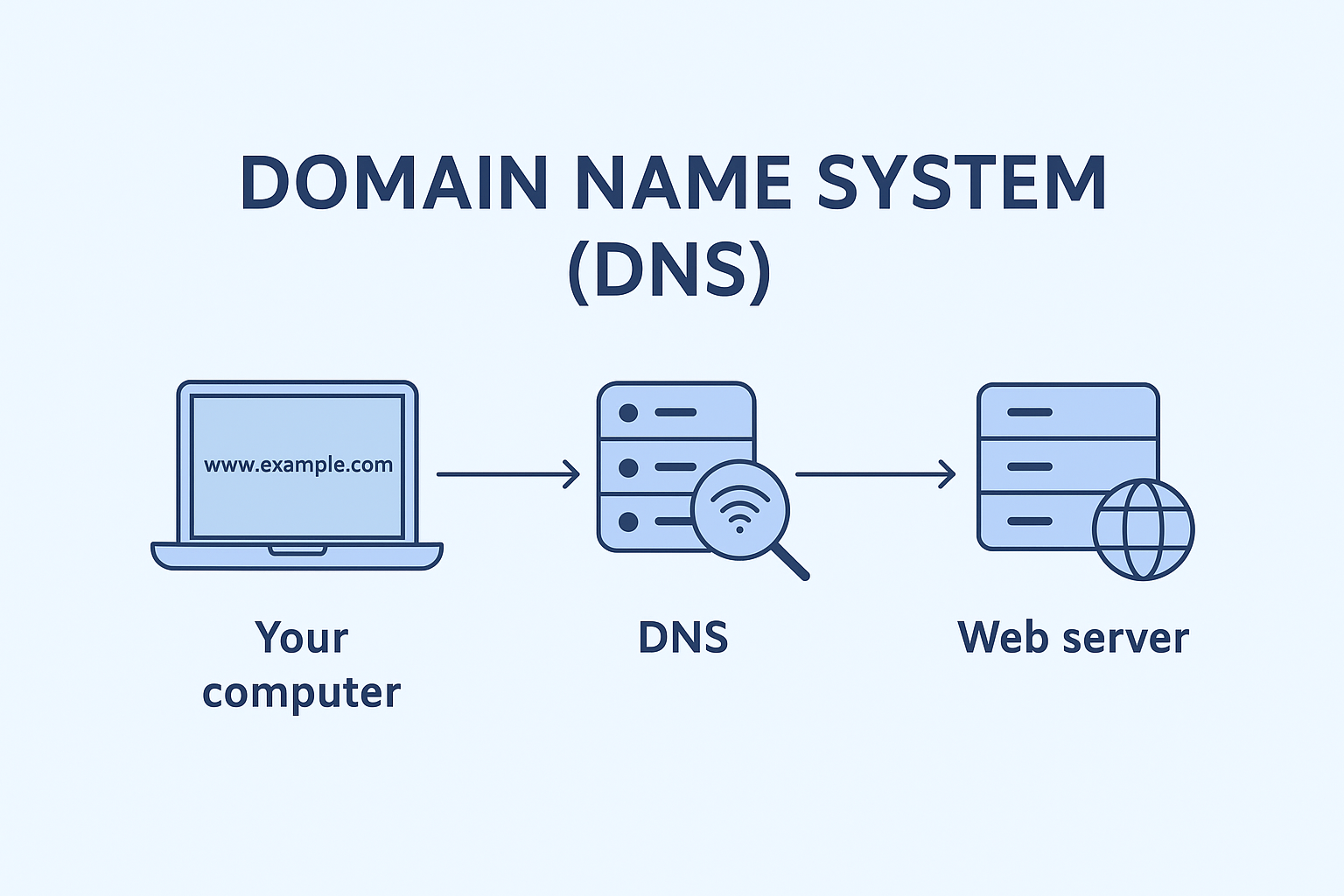

Every time you open a browser and type a website address like www.google.com, something incredible happens behind the scenes. Your computer somehow knows exactly where that website is located on the internet. But how does that magic happen?

The answer lies in one of the most essential systems that powers the web – the Domain Name System (DNS).

In simple words, DNS is like the internet’s phonebook. It converts easy-to-remember website names (like www.google.com) into machine-friendly IP addresses (like 142.250.183.132). Without DNS, we’d have to remember long strings of numbers to visit websites – which would be almost impossible!

Let’s explore what DNS is, how it works, which layer it operates on, what ports and protocols it uses, and why it’s so crucial for the internet.

Why Do We Need DNS?

Computers don’t understand names – they understand numbers. Each website, device, or server connected to the internet has a unique IP address, which works like a home address for data packets.

Now imagine having to remember 172.217.168.110 just to visit Google. That’s where DNS helps.

It acts as a translator that converts human-friendly names into numerical IP addresses, allowing you to use names while computers handle the numbers.

How DNS Works (Step by Step)

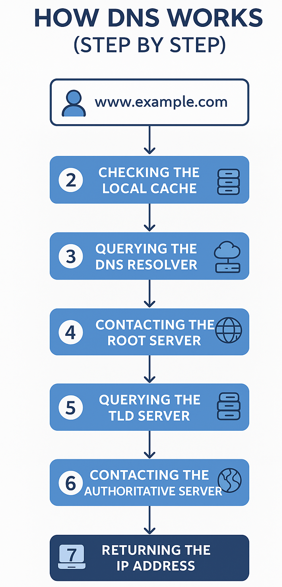

Here’s what happens behind the scenes when you type a web address into your browser:

1. You type a domain name

When you enter www.example.com into your browser, your computer needs to find out which IP address belongs to that domain.

2. Local DNS cache check

Your computer first checks its DNS cache – a memory that stores previously visited domain names and their IP addresses. If it finds the IP there, it connects directly to the website.

3. Querying the DNS Resolver

If your computer doesn’t know the IP, it contacts a DNS Resolver, usually provided by your Internet Service Provider (ISP) or a public DNS like Google’s 8.8.8.8.

4. Root Server lookup

The resolver asks the Root DNS Server, which knows where to find information for Top-Level Domains (TLDs) such as .com, .net, or .org.

5. TLD Server lookup

Next, the resolver contacts the TLD Server, which tells it where the Authoritative Name Server for the domain is located.

6. Authoritative Server lookup

The Authoritative DNS Server is the final source of truth. It stores the DNS records for the domain and returns the correct IP address – for example:

www.example.com → 93.184.216.34

7. Returning the result

The resolver sends the IP address back to your computer, and your browser connects to the website almost instantly.

All of these steps usually happen in just a few milliseconds!

Types of DNS Records

DNS records are instructions stored in the DNS database. They define how domain names should be handled. Here are the most common record types:

1. A Record (Address Record):

This is the most basic DNS record. It connects a domain name to an IPv4 address – for example, www.example.com → 93.184.216.34. This tells browsers where to find your website’s server.

2. AAAA Record (IPv6 Address Record):

Similar to an A record, the AAAA record maps a domain name to an IPv6 address – the newer, longer version of IP addressing, such as 2001:0db8::1.

3. CNAME Record (Canonical Name Record):

This record acts like an alias. It lets one domain name point to another. For instance, blog.example.com could point to www.example.com, so both lead to the same destination.

4. MX Record (Mail Exchange Record):

The MX record directs email messages to the right mail server for a domain. When someone sends an email to user@example.com, the MX record ensures it goes to the correct mail server, like mail.example.com.

5. TXT Record (Text Record):

A TXT record stores text information used for security and verification purposes. It can include SPF or DKIM entries to prevent spam or verify ownership with email and cloud providers.

6. NS Record (Name Server Record):

This record defines which servers are authoritative for a domain. These name servers store all other DNS records and respond to DNS queries for that domain.

Together, these records ensure your website, email, and services are correctly located and functional across the internet.

On Which Layer Does DNS Work?

DNS operates primarily at the Application Layer (Layer 7) of the OSI model.

Here’s why:

- The Application Layer is where user-facing network services work – like web browsers, email, and DNS.

- DNS provides a service to applications, helping them translate domain names into IP addresses so that lower layers (like the Transport and Network layers) can handle actual data delivery.

Even though DNS runs at the Application Layer, it interacts closely with the Transport Layer (Layer 4) and Network Layer (Layer 3) to send and receive messages efficiently.

Protocols and Ports Used by DNS

DNS communication mainly relies on UDP (User Datagram Protocol) and TCP (Transmission Control Protocol), both using port 53. Each serves a specific purpose depending on the type of DNS operation being performed.

UDP Port 53 – Fast and Lightweight Queries

For most DNS lookups, DNS uses UDP port 53. UDP is a connectionless protocol, which means it doesn’t establish a handshake before sending data. This makes it faster and more efficient for small, quick exchanges – exactly what most DNS queries are.

Typical DNS requests and responses are quite small (usually under 512 bytes), which easily fit within a single UDP packet. Because of this, using UDP minimizes delay and reduces network overhead, providing quick name resolution for everyday browsing and app connections.

TCP Port 53 – Reliable Data Transfers

DNS switches to TCP port 53 in a few specific situations that require more reliability or involve larger data transfers. For example:

- When the DNS response size exceeds the standard UDP packet limit (traditionally 512 bytes, but often higher with modern EDNS0 extensions), TCP is used to send the complete data.

- During zone transfers between DNS servers, where large amounts of DNS record data must be copied accurately, TCP ensures reliable delivery.

- If a DNS query sent over UDP fails, times out, or receives a truncated response, the client automatically retries the same query using TCP to retrieve the full result.

Speed vs. Reliability

In short, UDP is used for speed, handling the majority of everyday DNS lookups, while TCP is used for reliability when larger or more critical data must be exchanged.

This balance allows DNS to remain both efficient and dependable, ensuring quick responses for most users while maintaining accuracy when handling complex or high-volume DNS operations.

What Is a DNS Zone?

A DNS zone is a segment of the DNS database that contains all records for a domain and is managed by the domain owner. It defines how traffic should be directed for that domain – including website, mail, and subdomain details.

Recursive vs. Iterative Queries

There are two types of DNS lookups:

- Recursive Query: The DNS resolver takes full responsibility for finding the IP and returns the final answer to your computer.

- Iterative Query: The resolver gets partial answers from multiple servers step by step until it finds the final IP address.

Most modern DNS systems use recursive queries since they simplify the process for users and applications.

DNS and Security

DNS is critical, but it can be a target for attackers through techniques like DNS spoofing or cache poisoning, where fake DNS responses redirect users to malicious websites.

To prevent this, security features like DNSSEC (Domain Name System Security Extensions) add digital signatures to DNS records. This helps ensure the data hasn’t been tampered with and is authentic.

Real-Life Example

Suppose you visit www.cisco.com:

- You type the address into your browser.

- Your computer checks its DNS cache.

- If not found, your resolver queries the root → .com TLD → Cisco’s authoritative DNS server.

- The authoritative server replies with the IP address – for example, 72.163.4.185.

- Your browser connects to that IP, and the Cisco homepage appears.

All of this happens within milliseconds – almost instantly!

DNS in Everyday Life

DNS is always working in the background whenever you:

- Visit a website.

- Send an email.

- Use cloud-based apps or streaming services.

It silently keeps the internet connected and functional – translating names to IPs so that humans and machines can communicate easily.

Conclusion

DNS is the invisible backbone of the internet – converting user-friendly names into machine-readable addresses and ensuring seamless connectivity worldwide.

It operates at the Application Layer, primarily uses UDP port 53 (and sometimes TCP port 53) for communication, and forms the foundation for everything from browsing to emailing.